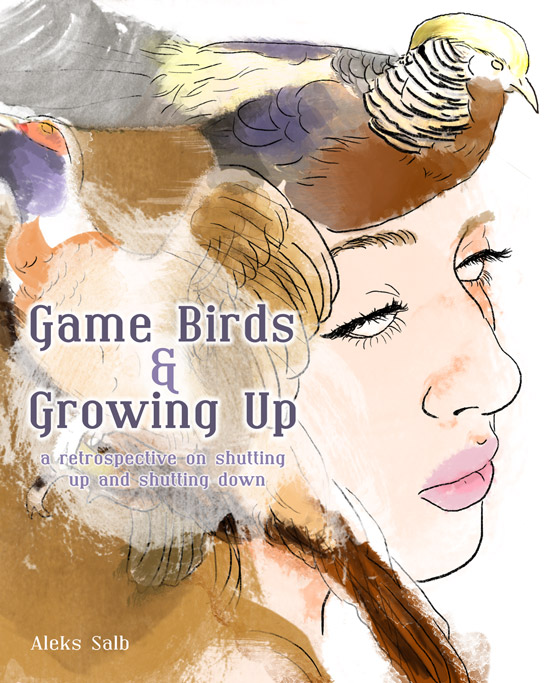

#TBT | Game Birds and Growing Up

T.O.F.U. has covered plenty of topics from a variety of people around the world over the years, but it’s the pieces that prove incredibly personal and emotional that often stand out in my mind. So, when I was putting together The Book of T.O.F.U. and picking some of my favourite pieces for the anthology, it wasn’t really a question whether or not to include Aleks’ piece from the sixth issue. Of course, having my own mother mention how it really hit home for her after she received the book in the mail made me realize it wasn’t just me who found the piece to be heartbreaking in a number of ways.

The version below is taken from the anthology and it differs from the original, which was published in 2011 and can be found here.

Trigger Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of violence against animals and mental anguish.

————

I grew up on a game bird hunting resort. Dad owned pens packed full of thousands of quail, pheasants, and chukar. Male pheasants were the trophy bird; they had ringed neck plumage, long tail feathers, and banded iridescent patches. Our main service was to take a requested number of these game birds out in bags, swing them around until they were too disoriented to fly right away, and then dump them into tall grass clumps in our fields. After a short wait, the hunters could bring their bird dogs and flush the birds out of the grass and into flight. They’d shoot the birds with 12 or 20 gauge shotguns.

We also had a 50-foot wooden tower along a tree line near the pond behind our house. We had a pulley to haul pheasants up in plastic cages. Around this tower were dozens of stations marked by hay bales where the hunters stood. We’d throw a pheasant off the top, and it would try to fly for cover. After we’d throw it off, we had to duck right away because about 30 eager people would start to shoot. Congressmen in particular liked tower hunts.

Once shot, birds would get stuffed into collection bags and brought back to our cleaning stations. We offered a dressing and packing service, so if they wanted, the hunters could carry the birds home to eat. A lot of the birds would only be wounded or still partially alive after being shot. We swung them by their necks to kill them. Nearly every day of the hunting season, I and a few hired help would be deploying, killing, and cutting up these game birds.

The birds were raised in captivity, but they weren’t like domestic birds. Pheasants are territorial and caging made them hyper-aggressive and neurotic. Blinders were stapled to their beaks to keep them from seeing what was in front of them and pecking or striking each other to death.

As for me, I was a labourer in an assembly line of death, or as I think of it, a dis-assembly line. We took lives and bodies apart. My childhood was like many family farms: you work where you live. You work for free and as much as you’re made to. On the plus side, there’s no commute. On the downside, there is no escape.

Truth is, I was bad at it. Pheasants were majestic and beautiful and wild and frightening. I wanted them to be free or just left alone. I hated the men, I hated killing and gutting things every day. Setting them in the hunting fields made me feel guilty. When their bodies returned in stained bags, it was mortifying and, depending on the carnage, revolting. Stripping their skin and cutting them up made me nauseated. Homeschooling meant I was always there, so what I didn’t do, I watched happen.

Sabotage was plotted every so often, and I got away with a few jailbreaks and equipment malfunctions. I staged crying fits and belligerence and became expert at hiding for hours in unlikely spaces. I was always dragged back and put to work again. I was the bad kid and nobody ever listened when I said this was a bad business.

To stay functional, I had to cope and distract myself from daily life. I’d hold my breath or cross my eyes, count or clench my teeth in different patterns. I controlled the few things I could with rigid severity. Every so often I’d try to fly off the tower.

The business wasn’t that profitable and my dad wasn’t great at running it. The hunters were mostly creeps, johns, pedophiles, businessmen and politicians, and more often than not those categories had some overlap. To survive was a type of success, but emotionally checking out was more immediately rewarding. Every hour of labour was double duty. There was the work, then work of shutting out what I did. Eventually I clenched and counted and closed my way into feeling less of anything, on any day. Pretending to be normal became normal then became nothing. My dad and his friends said I was growing up. I took their word for it.

I left that place the first chance I could. Fifteen.

While learning how to make choices and live with the ones that had been made for me, the anesthetic of growing up was slow to wear off. The walls and scaffolding I had built to survive didn’t just drop away when no longer needed, instead it morphed into other constructions. Mostly mausoleums. I had an obligation to house years of dead birds and long-dead parts of me. Empathy had been cut off at the source, so I had to pretend to be kind, since I knew how to pretend. Most of my feelings felt like imaginary friends. I recalled details, but not the feelings themselves. When I called for help, it was mostly to empty rooms.

I ran from a guilty past, but also chased it. I wanted to be vibrant and sensitive to myself, to other people and creatures again. But it was locked up in a kid on the other side of a painful history I was trying to erase. When I stopped eating meat, I actually worried I was deliberately weakening myself. I despaired that all those years of hardening might be for nothing and that the misery would go to waste. I couldn’t keep growing up and growing numb and couldn’t be that little loving person I remembered. Putting senses to sleep can be done through little tricks and bought time, but waking them up again, it seemed, would take earthquakes.

Written by Aleks Salb

Aleks Salb traveled across North America by bus, rail and car before eventually immigrating to Vancouver, British Columbia in 2012. He is currently celebrating his late-twenties, his recent marriage to a devastatingly handsome Russian gnome, and a blossoming career in social strategy. Current projects include memoirs of his life and a poetic translation of his paternal grandmother’s oral history.

Illustration by Kira Petersson-Martin